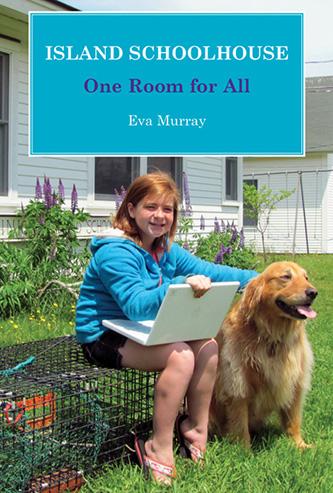

ROCKLAND — I sat down last week with local author and essayist Eva Murray, (Well Out To Sea: Year-Round on Matinicus Island, 2010), whose latest book, Island Schoolhouse: One Room For All, provides a fascinating look at one-room schoolhouses that still exist in Maine. The book goes beyond the quaint notion of the schoolhouse structure; it’s peppered with stories, anecdotes and history of the people who actually live on these island communities and how the school, as an entity, unites them.

In 1987, Murray moved to Matinicus to teach in a one-room school herself.

“It was just me,” she recalls, “like a Peace Corps posting.”

Instead of going back to the mainland for graduate school, she chose to stay on Matinicus where she married and raised a family. Over the last 26 years, she has started a small bakery, become an emergency medical technician, taken on a number of roles in municipal government and volunteer organizations, including serving on the school board, and started the community's recycling program. Those who enjoy Murray’s forthright, funny and tart columns about island life will find much of the same in Island Schoolhouse.

What did it take to go around and interview the schools in order to write the book?

The term ‘one-room schoolhouse’ has some vague borders around it. There are approximately six island schools we call one-room schoolhouses, but sometimes, a couple of them are actually two-room schools, depending on how many students they serve, any given year.

I started with my own experience as an island teacher and an islander. Then, to research the book, I did some formal and informal visits to the other islands, particularly Isle au Haut, Monhegan, Frenchboro, Cliff, and Little and Great Cranberry. I found out it was important to make several visits to each island, and this is why: like any community, each Maine island has had something happen in their past that was sort of painful. For example, Matinicus has a reputation for being a violent place. They had all been bullied, harassed and nagged by journalists before, so by the time I got there, a lot of people had pulled up the drawbridge. I had to get to know people on a more personal level in order for them to feel at ease that I was really interested in the school, the teaching, and not just the latest lobster war or whatever. It helped that I’d been an island parent, teacher and school board member, but it takes time to rebuild the burned bridges. So, it was very important that the research side of this book be done slowly and patiently.

What is the biggest misconception about a one-room schoolhouse?

That they don’t exist, anymore, or that they are a thing of the past. Some people just think of one-room schools as these old historic structures that have been preserved in many towns, with the old-timey elements like the separate boys’ and girls’ entrances, but my purpose was not to write about the architecture. Rather, this book is about the people still teaching and learning in our smallest schools.

There’s also the assumption that it isn’t real school if there are not 20 other kids of the same age doing the same thing — that teaching to one or two children somehow isn’t valid.

Then there’s the technology; people assume kids still write on slates. The fact is, we have the advantages of a rural environment and tiny community with lots of adult-to-child interaction and big kids helping the little kids, but we also have some of the most technologically advanced schools you will find anywhere. Almost every kid has access to his or her own laptop. They do a great deal of video conferencing and other online interaction. There are inter-island reading groups on Skype and an inter-island student council. There’s the Outer Islands Teaching And Learning Collaborative, where teachers and students from six one-room schools do academic work together. And not all of the children’s experiences together are on an island. The kids on all six islands will take field trips on the mainland; they’ve even all gone to Boston together.

There’s a section in your book titled THIS IS THE REAL WORLD with another subtitle: We are not Old Sturbridge Village. Talk a little about why some people view a one-room schoolhouse as sort of this anachronistic old-fashioned throwback to the book and TV show, Little House on the Prairie.

At some point, all of the island’s teachers and parents have heard, ‘But how is little Bobby going to manage when he grows up and has to go off island to deal with the Real World?’ The assumption is that an island education is not the real world. My angle is, anywhere where you have to deal with everything yourself.. .your kid gets sick, your roof leaks, your car dies, the groceries don’t get delivered from the mainland... you deal with it yourself. What could be more real than a place where you don’t have the option of calling someone on your smartphone and arranging for someone else to come fix your problems? The islands are perceived as a place to get away to on vacation. Most people for whom it is not vacation feel their world is the real world.

Island children can be members of the working community as soon as they self-identify as old enough; for example, they can start lobstering very young if that’s their thing, or start other small businesses, or help out with community needs.

If you’ve got a really motivated young person, he or she will often have more opportunities and fewer cultural obstacles than in some other places. I’ve seen elementary school-aged kids help out with all sorts of island events — both happy and difficult occasions. I don’t like to say they ‘grow up early,’ because people often misunderstand what that means, but they do learn a lot of real-world skills that some other children don’t have. Many island children can work, can drive and sometimes run a boat, can cook, and can help out in an emergency before they go off to high school.

There is so much to this book for educators, for Maine history buffs and for anyone who is interested in knowing how children thrive in this unique academic set up. To learn more about the book visit: Tilburyhouse.com

To find more about Eva Murray’s writings visit: evamurraywriting.com

Kay Stephens can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com