Long-lost scrimshaw finds way home from Maine to Alaska in time for Christmas

MAINE — An Alaskan artifact sitting in a building in Maine and awaiting the highest bid on Goodwill’s Northern New England eBay site was instead returned to its native family just before Christmas through a series of remarkable coincidences.

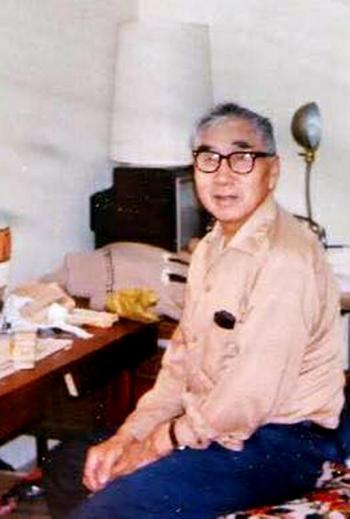

Thirty years ago, Teddy Sockpick, who lived in remote Northern Alaska, 200 miles south of the Arctic Circle, died of cancer. Sometime prior to his death, he took a 1-inch tall, 2.25-inch wide piece of walrus ivory and carved on it a Bering Strait scene, depicting three husky sled dogs in action, pulling a man and sled across the snowy terrain.

By unknown circumstances, that scrimshaw strayed from the family’s possession. Until, that is, a series of recent events.

A spirit within an item can move us

Teddy Sockpick’s granddaughter, Susan Ringstad Emery, has never been to Northern New England. Her Inupiaq and Scandinavian heritage remains deeply rooted in Washington State, where she was born, and in Alaska, where she spent a great deal of time throughout her upbringing.

Her interest, and therefore her art, remains with the people of those regions.

In November 2018, Emery flew to Anchorage to assist with cataloging Bering Strait native artifacts at Polar Lab Collective, within the Anchorage Museum and Smithsonian Arctic Studies Collections.

As she dug through hundreds of items, she sensed an emotional draw toward some of them.

“Some of the artifacts felt ‘meant’ for me to view and others decidedly not,” she said, corresponding in an email conversation, Maine to Alaska.

As another worker told her, “artifacts are alive and are waiting in the archives to be viewed.”

And then one day, the head curator, who’d been sorting and categorizing thousands, pinpointed a group of items on which Emery was to focus. Out of them all, one unlabeled artifact drew her closer. It was a bracelet showing a boat, a man, and an owl, and it seemed vaguely familiar. The initials of her grandfather — T.S. — etched on the bracelet confirmed her growing interest.

“I was deeply affected by finding my grandfather’s work in the collections and being able to identify it, bringing it out from obscurity,” she said. “I was left wondering if it had wanted to be discovered? My rational side doesn’t want to believe it, but the emotional side of my experiences with the artifacts at Polar Lab makes me think it’s possible.

“I shed tears later at my hotel room, as I started to process the experience of finding my grandfather’s artwork hidden away mutely in a drawer deep in the archives, and the way it connected me to my past and him.”

Born in 1907 or 1908, Teddy Sockpick had survived the Spanish Flu, which took the lives of his parents and siblings in 1918. He spent much of his life around Wales, Alaska, holding a deep respect to the land and heritage; his address for many years was “North Side of Only Street,” according to census records researched by journalist Julie Muhlstein, writing in the Everett Herald, The Herald.net, in Washington state.

“He was a thoughtful, quiet, hard-working and deeply caring man,” said Emery.

As he grew into adulthood the political and economic climate of the world began to change, even for those living in Northern Alaska.

He married a woman named Holly and the two produced a large family, which meant scraping together finances.

To Grandfather Teddy, creating art from the local ivory and capturing the scenes of his surroundings supplemented their income.

And it was one such piece, the bracelet, that had resurfaced in Emery’s hands decades later.

Days after Emery’s discovery, a 7.0 earthquake shook Anchorage, redistributing many of the artifacts within the storage bins of the museum.

At the end of November, Everett, Washington, journalist Muhlstein interviewed Emery at her Washington studio and wrote an article about the Smithsonian project. As the interviewee, Emery spoke of her grandfather and the bracelet that surfaced unexpectedly.

A few days later, Emery received a message on her Facebook page from a Chicago resident by the name of Anthony.

Anthony happened be surfing through collection of eBay auction items up for bidding through the Northern New England branch of Goodwill Industries, according to Emery.

When he came upon a certain, different, item, he contacted Emery. Indeed, he’d found another of Sockpick’s works. And, he said, he was was trying to win the bid in order to gift the scrimshaw back to the family.

“I was a bit dubious when Anthony’s message came through my art website,” Emery said. “He said he thought it was my grandfather’s work, but I didn’t want to get my hopes up. I was touched when he wrote that he had tried to win the online auction to restore the work to my family. In a world full of so much bad news, making us all cautious of strangers, it was remarkable to hear that a stranger was willing to go to such lengths for someone he’d never met.”

Anthony provided an attachment with a picture of the auction item — three sled dogs pulling a man through a snowy scene. It was one of many sled dog scenes Sockpick produced, illustrating the life of the Inupiaq people of the Arctic.

“Sled teams like this would be used to travel to other villages or to hunt for food during the long winter months,” Emery said.

Any one of the carvings may also have depicted a relative.

“Grandpa’s brother-in-law, Herbert Nayokpuk, was a well-known and beloved Iditarod dog sled racer, who is now in the Iditarod Hall of Fame,” she said.

Uncle Carson Sockpick said of his father, Teddy: “His best time was when he was able to go boating for commercial fishing and seal hunting in his 18-foot boat, sometimes boating for over a 100 miles in rough seas. He never said no to any hunter who asked to come along knowing he was very careful about the weather and ice conditions.”

Cousin Cindy Allred’s memory of Teddy Sockpick: “My strongest memories of him are when he would take me fishing with him with a net. There would be fish flopping all around our feet. I remember getting disoriented and having no idea how to get back to land, but he always knew the way.”

The art of scrimshaw requires much attention to detail.

“It would be a process of hours, involving cutting an even thin cross section of the fossil ivory with hand tools, and smoothing the raw surface to the point where it was smooth and shiny,” she said. “The meticulous etching on the surface requires a steady hand and an eye for drawing. Once the etching was complete, ink would be rubbed into the cut grooves. The piece would then be polished once again and fitted with findings as needed, such as pendant rings, earring hooks, brooch pin backs, or drilled to thread with elastic cord if it was a bracelet of many tiles.”

Bidding of the item, through the Goodwill website, came to an abrupt halt at the Goodwill site, however, when Goodwill was notified that the item was made of ivory.

Heather Steeves, of Goodwill Northern New England, in Portland, said: “When we got the piece, we thought it was made of antler, which isn’t uncommon here in Maine. A customer saw the posting on eBay and wrote to us telling us it was ivory and we immediately pulled the listing from the site. We do not sell ivory.”

However, in this case, Goodwill was happy to return it to its owners, Steeves said.

On December 15, the artifact that made it’s way to Maine through unknown circumstances returned home to Alaska.

“To later have an ivory scrimshaw carving of my grandfather’s identify itself in Maine, and through remarkable circumstances, to come home to me, gave me a deep feeling of completion and satisfaction,” said Energy. “Did the artifact from Maine want to come back to where it belonged? I can’t help but think it is at ‘rest’ now surrounded by the works of Grandfather’s late brother-in-law Herbert and grandson Thomas and in the home of his eldest granddaughter.”

Reach Sarah Thompson at news@penbaypilot.com