Several years ago, as part of the upgrade in service when “911” was officially designated the emergency number for the country, every road had to have a name and every dwelling a street number, so that emergency responders could easily find them. For us it meant that after thirty years of living on Route 173 with a box number for our mail, we found ourselves at 217 Beach Road. The main roads were given the name of their destination away from Lincolnville Center: Route 52 became Camden Road on one side of the Center, Belfast Road on the other. Route 173 was Beach on one side and Searsmont Road on the other, and 235 became Hope Road. A few other town-maintained roads already carried names – Youngtown, Slab City, High Street, Moody Mountain, etc. And one, an out of the way road that dissolves into an impassable woods road for part of its length, also kept its traditional name: Masalin Road.

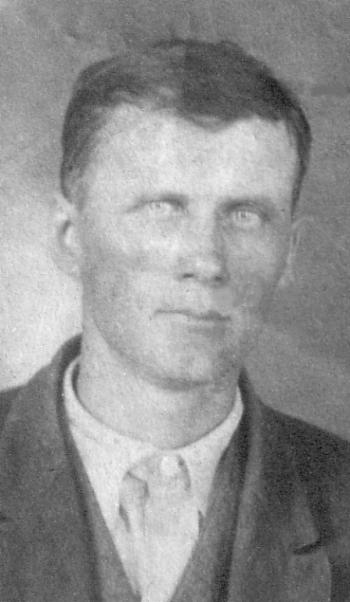

Some 15 years ago, as an essentially dead end road, it was a pretty quiet place with only a handful of houses. It still doesn’t go through from one end of it to the other, but several more houses have been built up there, and part of it has been paved. Here’s the story of how it got its name, long ago, from the family that settled there in 1923:

The sun was finally high enough in the sky for the melting to begin. Ossian Masalin paused in his shoveling to look up at the eaves of his barn, where the drops of melting snow flashed in the winter sunlight. That had been some storm, he thought, a good two days of snow, the howling wind pushing it into high, shifting drifts. He and his boys had just managed to make it to the barn and back for chores each morning and evening, their footsteps nearly obliterated in minutes. Today, which dawned bright and clear, they had wasted no time tackling the nearly three feet of snow blanketing the farm.

After two idle days shut inside, both Reino and Fannie were actually eager to go back to school. When Ossian said Reino had to stay home and shovel, the 13-year-old had grumbled a bit, especially watching his younger sister strap on her wooden skis and take off down the road to the Miller School, a mile away. At nine Fannie was quite independent, and didn’t need her older brother’s company; her friend, Mildred Lermond, would meet her part way.

Ossian checked his pocket watch. Susanna should have the coffee ready by now, but he’d let the boys work a few minutes more before calling them in. He leaned back against the pile of snow he’d thrown up against the barn, and squinted at the sky. The sun felt hot on his face, sweaty from exertion in spite of the cold temperature. He watched his sons working steadily on the road into the farm. Ero at 16 and Viljo at 15 were both strong, strapping boys, but still it would take them all day to shovel out, even with Reino helping too. As hard as they worked when they had to, he doubted they would ever face the hardships he’d known.

Ossian, born in Vitasaari, Finland, was only a year or two older than Ero when he’d realized his homeland didn’t offer a promising future. The threat of conscription into the Russian army was hanging over the heads of young Finns when he made up his mind to come to America. In 1900 Ossian crossed the ocean and entered the country through Portland, Maine, then traveled north to work in the lumber camps; he was just 18.

The next few years were a blur in his memory now, years of traveling and working at hard, manual labor. After a winter in the north woods of Maine he’d gone to Washington and Oregon where he fished, then down to California redwood country and another lumber camp.

By 1903 he was in Hanna, Wyoming, working as a coal miner. Even now, 20 years and thousands of miles away, he felt a shiver of horror at the thought of Hanna, Wyoming. He wasn’t in the mine that hot June morning, or he wouldn’t be here for this cold and snowy one. He hadn’t seen the flames shooting out when the mine exploded or the mangled bodies of the dead and injured, or the way the mouth of the mine looked after the blast, buried in 25 feet of debris—timbers, rock and dirt. What he had seen was the effect of that day on his wife.

For Susanna was someone else’s wife that day—Jacob Niemisto’s, the man she’d left Finland to marry. And Jacob had been in Hanna Mine No. 1 on June 30, 1903. Working next to Jacob that morning was the husband of Susanna’s sister, Maria. The two sisters had traveled together from Finland with such high hopes, each to marry men who had emigrated earlier. After that, Maria could no longer see a future for herself and her child in America, so she returned to Finland. And Susanna found herself alone with 18-month-old Inez.

By 1905 Ossian and Susanna had met and wed. Both were eager to leave Hanna behind them. They heard talk of the Iron Range in northern Minnesota, where people were so rich they stuck silver dollars to the side of their houses. By then both Ossian and Susanna had seen enough of America to know such stories were just that. Still, they packed their few belongings and with little Inez got on the Union Pacific train headed east to the iron mining town of Virginia, Minnesota. Once there they weren’t surprised at all to find out the “silver dollars” were just the pieces of tin people used to hold up the tarpaper on the walls.

The town’s streets were lined with boarding houses, tall four-story buildings where the mostly immigrant miners and sawmill workers lived. Ossian had no intention of going near a mine, even an open-pit mine. Before long he and Susanna found themselves running one of the Finnish boarding houses. Susanna cooked the meals that were served family style in the plain dining room, while Ossian kept the woodstoves supplied, and the building in repair.

With so many men either unmarried or living far from their wives and families, Virginia could be a rough place in spite of the strong temperance movement among some Finns. Ossian had a wife and child to be responsible for now, and watching the hard-working and sometimes hard-drinking men in the boarding house, he realized this wasn’t the life he wanted for his family. Better to settle down on a piece of land in the country.

He remembered Maine, the first place he’d seen in America. It had looked a lot like home with the sea, rock and forest. Susanna, who had given birth to Ero in the winter of 1907, wasn’t happy about leaving the security of Virginia’s Finnish community for the uncertainty of another new home, but it was Ossian’s decision to make. So, with Ero in her arms and little Inez clinging to her skirt, she traveled with her husband to Ash Point on the coast of Maine. In fact, there was a large population of Finns in the area, and Susanna settled in. Here the rest of her children were born: Viljo in 1908, Reino in 1911, Fannie in 1914 and Veino in 1922.

Then, after some 15 years in Ash Point, first scalloping from a boat he built himself, then going to the Grand Banks on a trawler, and finally doing the backbreaking work of a quarryman, Ossian wanted a chance to farm. The small place he owned could never support a growing family, so when he heard about an elderly couple looking to swap a 300-acre hill farm in Lincolnville for something smaller in Ash Point, Ossian grabbed it. The farm was theirs through a trade, although not an even trade. He’d paid nearly $3,000 cash in addition to the Ash Point place. It was a deal he’d sealed without his wife, for once again, Susanna was being uprooted from a community of Finnish-speaking friends and neighbors.

Ossian walked around the corner of the barn and looked at the long stretch of house and shed, buried under two feet of snow. He thought about the summer day, some six months ago, when he’d brought Susanna and the younger children up from Ash Point. He’d been living on the farm with Ero and Viljo since spring, but his wife stayed behind while Fannie and Reino finished the school term. Baby Veino rode in the cab with him and Susanna, while Fannie rode with the furniture. The trip was uneventful, though Susanna protested at the narrow road along Megunticook Lake. Once they’d arrived at the farm she promptly walked all through the house, looking behind the doors and in the cupboards, checking the solidness of the floors, the tightness of the latches.

He’d worried some at how his wife would take to the new place. Now, she’d have to learn English. It was too easy for her in Ash Point with so many Finnish neighbors. The children were growing up speaking English, though of course, they still spoke Finnish as home with their mother.

Ossian shook his head. He’d been staring into the past so hard he didn’t see that his sons had the driveway almost clear. He’d be able to get the pung out onto the road today after all, loaded with milk and cream for the Hood dairy in Belfast.

Find Susanna Masalin’s receipe for Finnish Nisua, a favorite bread served with coffee, in Staying Put in Lincolnville, Maine 1900-1950, available at Western Auto and at Sleepy Hollow Rag Rugs, both on Beach Road in Lincolnville.

A funny exchange at last week’s Library program between the speaker, Tom Sadowski, and an audience member got me thinking about Ossian and Susanna Masalin. Tom, whose parents were Polish, had told us he was five years old before he began speaking English. A friend, who later emailed this to me, came up to him after his talk to share her experience.

“My parents spoke Polish growing up, but only when they wanted to say something in secret. Even so, I learned just a few words. I told Tom after his presentation that I knew “dahmi boushee” which means “give me a kiss’. Then I said ‘shviniah’ which I told him I thought meant ‘brother-in-law’. That is what my Dad always called my uncle when he spoke of him. Tom did a double take and then told me ‘shiniah’ means ‘pig’. LOL - they did not get along my uncle and dad!”

And that’s when I thought of Susanna Masalin, living on the to-be-named Masalin Road, her only neighbors, Downeast Yankee speakers. According to her granddaughter, Joan Masalin Ratliff, she never learned English, and missed the Finnish-speaking communities she’d always lived in. The trials she and Ossian went through on the path to their farm in Lincolnville aren’t unlike those of today’s immigrants to Maine — Africans and Iraqis and Latinos and others. Hopefully, in years to come, communities all over the state will have roads named in their honor.

As I write this Monday morning “one of the biggest storms in history” is predicted for the North East. We’ve heard that before. Maybe for NYC and Boston, but I’ll be surprised if it follows through all the way up the coast. Still, we’re gathering supplies – lamp oil, an extra flashlight, buckets of water, gas for the snow blower, etc. etc. The Halloween storm caught us all unawares, so we’re taking no chances.

From the Town Office: “If you haven’t already licensed your dog you have five days remaining to do so before the State mandated late fee of $25 is charged.”

Thursday, noon to 1 p.m. hot soup is on at the Community Building; all are welcome for a free lunch (donations, if you wish to make one, go to the UCC’s Good Neighbor Fund). Stop by for a homemade meal, good company, and sometimes, live music.

A Contra Dance will be held on January 30, 7 p.m., as part of the Fifth Friday series of Contra Dances at the Community Building, 18 Searsmont Road (Route 173), with caller John McIntire backed up by the Reunion Band. This dance is second in a series to be held throughout the coming year at the Community Building, which was a popular site on the dance circuit many years ago, and now is reviving the tradition. All ages are welcome; $8 per person, $15 for a family. All dances are taught. Wally and I had somehow never been to a contra dance in spite of the1970s. We went to the one held last month at the CB and had a great time! Contact Susan or Jack Silverio for more information, 763-4652.

Saturday January 31 the Appleton Library holds its annual “Souper Supper” at the Appleton Village School, 5-7:30 p.m. with Rosey Gerry officiating at the Cake Auction. Admission is $8 for adults, children 5-11 $5, and under 5 free. Contact Debby Keiran, 975-1424 for more information.

Calendar

MONDAY, JAN. 26

Selectmen meet, 6 p.m., Town Office

TUESDAY, JAN. 27

Lakes & Ponds Committee, 7 p.m., Town Office

WEDNESDAY, JAN. 28

Total Body Energized Fitness Class, 10-11:15 a.m., Community Building

Planning Board, 7 p.m., Town Office

THURSDAY, JAN. 29

Free Soup Café, noon-1 p.m., Community Building, 18 Searsmont Road

Dynamic Duo Fitness Class for balance & flexibility, 1:15-2 p.m., Community Building

FRIDAY, JAN. 30

Contra Dance, 7 p.m., Community Building

SUNDAY, FEB. 1, Guest Preacher T.J. Mack, 9:30 a.m., United Christian Church, 18 Searsmont Road

Every week

AA meetings, Tuesdays & Fridays at 12:15 p.m., Wednesdays & Sundays at 6 p.m.,United Christian Church

Lincolnville Community Library, open Tuesdays, 4-7, Wednesdays, 2-7, Fridays and Saturdays, 9 a.m.-noon. For information call 763-4343.

Schoolhouse Museum open by appointment only until June 2015: call Connie Parker, 789-5984

Soup Café, Thursdays, noon-1 p.m., Community Building, free (donations appreciated)

Corelyn Senn has been writing a column on Lincolnville’s cemeteries in The Camden Herald for the past year or so, and several of them now available on the Lincolnville Historical Society’s website. Corelyn researches the history of each cemetery, its origins as a burying ground, and who owned it. Interesting gravestones are featured, along with their epitaphs, and other details she uncovers in her research. Eventually, all the graveyards, from the single graves found around town to the abandoned cemeteries to the currently-in-use ones will have their story told. Corelyn is always interested in hearing from people who have information on them.

Gardeners (and I imagine, farmers) are a breed apart in our modern world where time for most is marked by paid holidays/long week-ends, or by sales cycles such as Christmas/back-to-school/Presidents’ Day, or by the school calendar, or the Social Security check. Each phase of life or occupation marks time in its own way. For us gardeners it’s the seasons, of course, for obviously things happen in the garden depending on the weather. But even we have our artificial markers; for instance, the arrival of the seed catalogs in late December gets our hearts pumping. Funny how the seed companies, which used to wait until after the new year, now fill our mailboxes alongside the Christmas cards.

This year I got my order in early, and just the other day a fat, little box arrived full of my hopes and dreams for next summer’s garden. I order most everything from Fedco Seeds, though there are so many good seed companies out there, and we all have our favorites. Last fall we walked around our garden and made a map of where stuff should go this year. Maybe I’ll plant the celery and onion seeds during the blizzard.

A couple of friends spent six hours in the Philadelphia airport last week, a scheduled layover that quickly became tedious. They wandered all over the terminal, as you do during those long hours between flights, and finally settled in at the gate with the flight going to Bangor. They knew they were at the right gate and on their way home when they spotted three women knitting. Not in a group, just three individual women knitting, the only ones they saw doing that in the whole airport.

Walking our dog, Fritz, over on Ducktrap Road a couple of days ago we spotted a mink down by the little brook that flows into Frohock. We watched it for a while as it darted under the ice, then back up, behind trees, over roots. That makes four minks in the past week, though only the first we’ve seen. Richard Glock had a mink on his back deck one day, then Ruth Felton reported one on her deck; that one ran right near her foot, then darted down into the rock wall that runs out from her house, (the wall her father built some 70 years ago). Finally, another friend thought she had a black rat in her garage, but after I sent her a photo of a mink she decided it might have been that. She compared mink tracks to some mysterious tracks on her deck and yes, they were from a mink. She’d been tossing bread crumbs out for the mice to eat, and decided the mink was probably feasting on bread-stuffed mice. Keep your eye out for these small, sleek little creatures, nearly black, and very quick. You often see them near water; I never knew they’d come so close to a house.

Lincolnville Resources

Town Office: 493 Hope Road, 763-3555

Lincolnville Fire Department: 470 Camden Road, non-emergency 542-8585, 763-3898, 763-3320

Fire Permits: 763-4001 or 789-5999

Lincolnville Community Library: 208 Main Street, 763-4343

Lincolnville Historical Society: LHS, 33 Beach Road, 789-5445

Lincolnville Central School: LCS, 523 Hope Road, 763-3366

Lincolnville Boat Club, 207 Main Street, 975-4916

Bayshore Baptist Church, 2636 Atlantic Highway, 789-5859, 9:30 Sunday School, 11 Worship

Crossroads Community Baptist Church, meets at LCS, 763-3551, 11:00 Worship

United Christian Church, 763-4526, 18 Searsmont Road, 9:30 Worship

Contact person to rent for private occasions:

Community Building: 18 Searsmont Road, Diane O’Brien, 789-5987

Lincolnville Improvement Association: LIA, 33 Beach Road, Bob Plausse, 789-5811

Tranquility Grange: 2171 Belfast Road, Rosemary Winslow, 763-3343