TENANTS HARBOR — There are three surprising facts about granite, that white, pink or grey igneous rock so highly prized for its beauty and strength in architecture.

“One, it’s fragile,” said Steve Lindsay, a granite sculptor in Tenants Harbor. “If you have a 12-foot long step, you have to be very careful when you move it, because it will snap. People forget that it has no tensile strength, so if you look at all of the granite posts along Main Street in Rockland, you’ll see a lot of them have been repeatedly hit and damaged by cars and repaired with a cement base. Two, granite is not fireproof. If it has been in a fire, the granite is ruined, because it holds water within the grain, so when the water turns to steam, it shatters the rock. The last thing, is granite is light. People don’t think it would be, but it actually has the same density as aluminum.”

A history buff on local granite, Lindsay recently gave a talk to a packed audience at the St. George Historical Society on Midcoast granite quarrying and gave a demonstration on his stone-cutting technique.

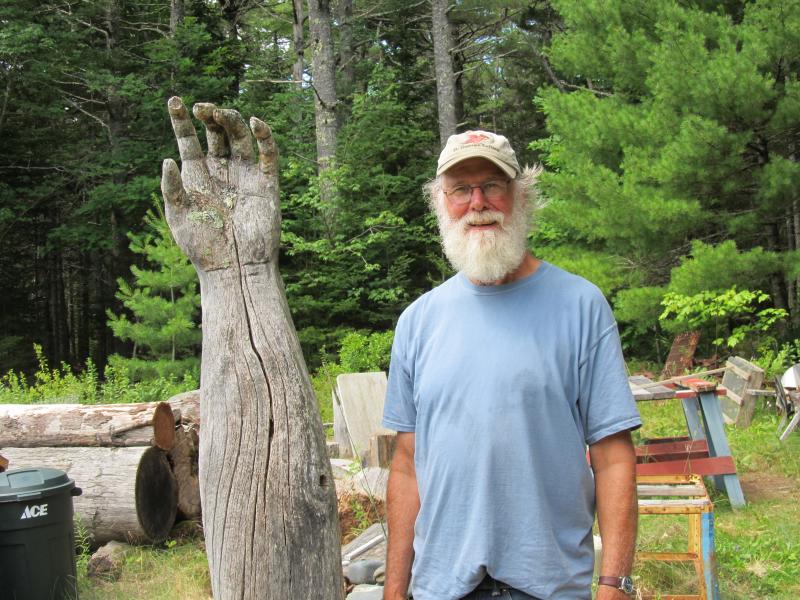

He grew up in Long Island, and studied and worked in Massachusetts, New York City and Canada before moving to Maine in the mid-1970s. At that point, he was primarily a wood sculptor, until one day he came across the Andre The Seal granite statue carved by sculptor Jane Wasey.

In the 1970s, granite sculptors were relatively few and far between in the Midcoast and Lindsay became fascinated with learning how to carve the stone.

“I learned that the original stone cutting tools for Maine’s coastal and island granite quarries were made right here in Rockland by the Bicknell Supply Company, so I bought my first tools directly from them,” he said.

In St. George, there are several large quarries, including a Black Granite quarry, which yields beautiful grey to black stone. But Lindsay started his granite carving practice with essentially found materials.

“Over the years, I’d go to the homes of people who owned old quarries,” he said. “They’d let me come out and select pieces of stone. The trick was getting them out of there by hand. Now, I have a tractor, but then, I was cutting it by hand and used a hand truck.”

On the back of his property sits a reclaimed shed-roofed shack, which he rebuilt himself into a shop. Large garage windows illuminate the studio, which looks like a miniature version of Liberty Tool with every square inch of space dominated by carving tools. He uses carbide tipped chisels “which are harder than tempered steel, the traditional tool for carving granite,” he said.

He purchased most of his own tools over the years, but quite a few friends have donated them to his shop.

Lindsay explained that granite became the most coveted material for buildings in Maine and around the nation after the Civil War, as it became a symbol for wealth and endurance.

“Entire buildings like a six-story building on Wall Street would come from Maine’s quarries, with figure carvings all around them,” he said. “Everything was cut exactly to size here, crated and shipped on schooners to cities. The only way to move it was by water.”

Locally, these natural resources made valuable building material as well with many federal and public buildings constructed to reflect the wealth of the times. The Custom House and Post Office in Rockland was built from granite in 1898 from the St. George quarries before it was demolished in 1969.

The Rockland Breakwater, is another enduring testimony to locally quarried granite. It took 10 years to build with gigantic granite blocks brought over from the Vinalhaven quarry.

“They’d bring one piece at a time by sailboat and drop it into the harbor,” he said. “Later, they did it by barge.”

A walk around his property reveals several wooden sculptures and granite slabs, which have been rendered with intricate designs. Much of his art is representational, and ranges from portraits to gargoyles; from small delicate carvings to over-lifesize figures hewn from massive logs. Lindsay is not carving much at this point, but he has had numerous shows in galleries and all over Maine and the world. For more information about his work and sculptures visit: http://www.stevelindsay.net

Kay Stephens can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com