The waiter thought he was being helpful.

One afternoon after teaching a class in New York City, Norbert Nathanson thought he’d treat himself to a T-bone steak and found a restaurant he thought he’d enjoy. As he walked in, he could sense the waiter’s overly solicitous manner.

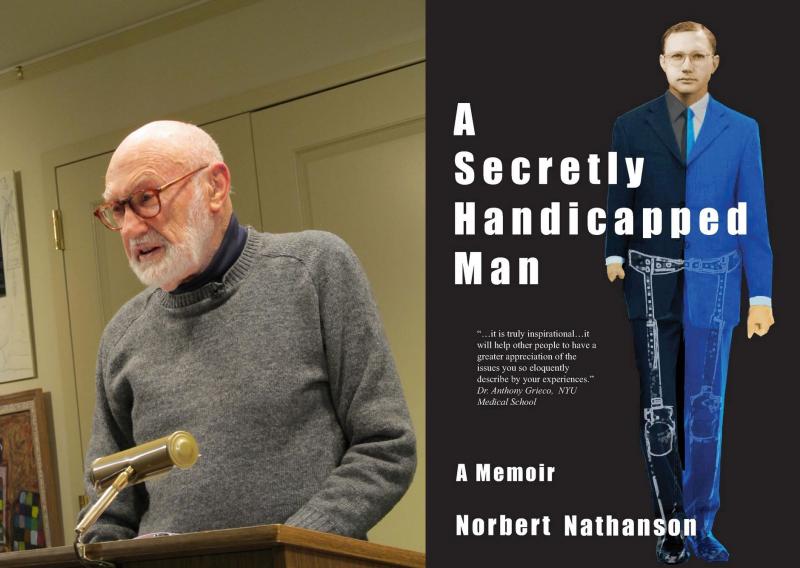

“I’m always interested how long it takes the average person—the doorman, the salesperson, the waiter—to notice the absence of my right hand,” said Nathanson, reading from his first memoir, A Secretly Handicapped Man at the Camden Public Library on Thursday, Dec. 12.

“With an exaggerated flourish, he showed me to a table, pulled out my chair, unfolded a napkin, and handed me the menu. And there he stood, smiling, hovering over me. People who want to be helpful are frequently clumsy and awkward around me. He left me to peruse the menu and when he came back, he removed my water glass from the right side of the table to the left. And then he rearranged the silverware and artificial flowers on the table. When I was ready to order, I closed the menu and he was back at my side. I ordered the steak, medium rare, baked potato and salad and he hovered for a moment, studying my hand, and satisfied that everything was in order, smiled at me and disappeared into the kitchen. Repeated and unneeded attention to my disability frustrates me,” said Nathanson in his calm way.

When the waiter arrived with his steak, he picked up Nathanson’s knife and fork “assuming the offer would be readily accepted” to cut his steak for him. Politely but firmly, Nathanson let him know he was fine. “I’m known to respond in ways that tend to surprise people. I’m quite skillful at dealing with my disability.”

He described how he ate his meal, quite contentedly. Noticing the waiter watching him from the small window of the swinging door to the kitchen, Nathanson said, “I decided come hell or high water, I wasn’t going to let him see how I cut this steak.”

That last line was met with chuckles from the audience. For nondisabled people, however, there is a tendency when encountering a disabled person for the first time to be overly helpful. It’s different from being courteous (perhaps opening a door or asking first if one needs help at all); it’s more of an assumption—that the disabled person requires a stranger’s help to get through life. An assumption like this, as well meaning as it is, is likely to tread on the disabled person’s dignity.

Mr. Nathanson offered some insights like this and much more as he spoke before a dozen or so people in the audience. Nathanson, born with no feet and with only one hand, had spent the last 34 years struggling to be accepted by society while finding his way in the world. Growing up in the working class of Depression era Pittsburgh, he had a hard time finding fulltime employment, trying desperately to enter the new field of television.

In the early 1960s, he met a man who would change his life. Dr. Allen Russek from the New York University Physical Therapy Program, examined his withered shins. The terminus of each leg was ensconced in special orthopedic shoes, which bore the brunt of Nathanson’s full weight. But in addition to the stares, epithets and social rejection he constantly endured, Nathanson was always in chronic pain. Dr. Russek let him know that advances in medical science could provide him with artificial legs, which would give him a natural appearance. In order to do this, however, Nathanson would have to make the choice to have his legs amputated below the knee.

Nathanson went ahead with the surgery, and fitted with prosthetic legs, he stood at a normal height, walked with a normal gait, and could keep his disability a secret, permitting him for the first time, to enjoy life-altering public anonymity. Being out of the spotlight of public stigma brought him peace. His career blossomed.

Until the publication of the book, he’d never shared his story, and held his secrets fiercely. He has never seen himself as being different, nor has he defined himself in dramatic terms. An experienced, serious, and driven educator and television executive, outdoorsman, sailor, carpenter, fisherman, he has formed his reality. He frequently speaks to college audiences, including occupational therapy students about how to treat the disabled.

After his compelling book reading we asked him to further elaborate on some of the issues he spoke about in his book.

A: Yes. I had some concerns. I started to write a journal just for my children, so they would know about my difficult life before they knew me, particularly in view of Erving Goffman's theories, about how societies treat those they have stigmatized. Readers of my manuscript, professionals all, urged me to publish on the grounds that the book would be of use to those whose lives had been touched with disability. I had gone through a similar situation in 1982-1983 when I, as executive producer at WMHT, Schenectady, had produced a series of four programs about disability which won honors in California. I was a reluctant host and interviewer and could not speak of my guests as "them." It had to be "us."

Q: In the course of your life, you have been variously labeled as "crippled, deformed, handicapped, and disabled, more recently as a person with disabilities, and currently as physically challenged." How do you feel about these evolving terms and is there a word or a phrase that you would use in place of any of these?

A: Epithet. They all mean "different" and society needs to identify the disabled in what it considers polite terms so it provides an easily used identifier, an epithet. Over time these reveal society's changing perception.

Q: In your talk, you discussed how your disabilities allowed you a larger perspective of societal norms, particularly around the notion of stigma, of "physically branding people who are different." What have you learned that you could you share and explain to say, a nine-year-old kid, who may not have absorbed these societal values yet?

A: That it is critical to not "label" or "categorize" people.

Q: Another element of your disability was chronic pain—not being able to stand or walk for long periods of time without a gnawing agony. Can you explain what kind of stamina, energy and stoicism you had to possess to get through a job interview (already a stressful situation)?

A: I suppose it would have to be determination, a will to succeed sufficiently strong to overcome the difficulties.

A: I had lived, based on my experience, within what I perceived to be the limits of my physical disabilities and potential, and had made peace with what I perceived as my future and my life expectancies, but I dreamed beyond it. When I learned that there was a good chance that my assumptions were wrong, that my physical condition would get worse, but that my dreams could actually be realized, it was a relatively easy decision. As I wrote: "The quid pro quo is, very simply, the traumatic experience of surgical amputation vs. the will to function and appear normal. The former is something no rational person approaches without some degree of trepidation; the latter something no disabled person does not dream about."

Q: With all of your lifelong accomplishments, (educator and television executive, outdoorsman, sailor, carpenter, fisherman) you can now add "author" to your resume. What's the book tour been like so far?

A: I have no "book tour." I am not personally selling books. I had planned to do so and had sought out my publisher to help me ready my manuscript for self publishing, decided against it, and she decided to publish it. In October, I spoke to undergrad and grad student therapists (occupational, physical, psychology) at Ithaca College at their invitation, and had done so in previous years at Husson College. And I spoke in Camden. I've no other plans, but have had good press and Internet visibility.

Q: Today, what gives you the greatest feeling in the world, the most peace, the most happiness?

A: Given my disabilities, I had never expected to live as long as I have. I'm thankful for that, and for having experienced a miracle, and for had the privilege of working and making my living, when I was able to do so, at work I loved doing. I'm thankful too, to have survived, but most importantly, to have been able to do so with a loving wife and children, one of whom, our daughter, we lost to breast cancer 2 1/2 years ago.

To find Nathanson’s book on Amazon visit: amazon.com/Secretly-Handicapped-Man-Memoir/dp/0989568911

Photos and video courtesy Norbert Nathanson

Kay Stephens can be found at news@penbaypilot.com