The country doctor's progress

BELFAST - Early in his book What Matters in Medicine: Lessons from a Life in Primary Care, David Loxterkamp says that for as long as he could remember he wanted to be a doctor like his father Edward Otto Loxterkamp. It’s a claim that would sound glib if not for the striking similarities between their lives and the generational parallels within the profession they both chose.

His book chronicles his journey, from a boyhood fascination with his father's career to the life he’s built in Belfast as a physician and community member.

Ed Loxterkamp's career in the 1950s and ‘60s spanned a period of decline in the field of general practice. The old model of the “country doctor” with his signature black bag had been losing ground to specialization since the end of World War II. It was also on the cusp of being revived by a generation of young doctors who would reject the rat race of urban hospitals in search of something more essential in medicine.

Though Ed Loxterkamp didn't live to witness the revival, it was accounts of doctors like him, working in rural areas, often alone, that emboldened a new generation to take up the cause of general practice medicine under the new name "family practice."

David Loxterkamp was among them, and he names his father as one of three major influences in his approach to medicine.

The other two were Ernest Ceriani, a doctor in rural Colorado and subject of 1948 photo essay by Eugene Smith that appeared on the cover of Life magazine, and John Eskell the English physician at the center of John Berger and Jean Mohr’s book A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor.

Their stories would be familiar to any physician of Loxterkamp’s generation, and though the depictions were not glamorous — if anything, they were brutally realistic — they painted a clear picture of general practice as noble work. Ceriani and Eskell were cast front and center as the heroes of their respective stories. Like many artists of the same time period, they worked alone.

As Loxterkamp would later find out, the qualities that made Ceriani and Eskell inspiring ultimately worked against them, leaving them isolated and estranged from the communities they had served.

Writing at a similar time in his own career, Loxterkamp advocates for what the doctors of his father’s generation failed to see, whether out of pride or professional detachment — that the community depends on the doctor for its survival, but the opposite is also true.

“When we finally realize that we have ‘earned’ our place in community,” he writes, “it liberates us from the compulsion to achieve, impress, ingratiate, or leverage ourselves for the purpose of being liked and accepted … Eventually a friend will scorn us, and an enemy will stop to help us along the side of the road. We learn to rise above our embarrassments and shame just like everyone else. We exchange a sense of the place for our place within a welcoming and accepting community.”

What Matters in Medicine is laid out in three sections describing a beginning, middle and end. But as Loxterkamp makes clear, the bookends mark only his own experience within an ongoing cycle that continues to evolve.

PenBay Pilot recently sat down to talk with him about his book, the current state of patient care, and his place within that cycle.

What is the “medical home?"

What the medical home is trying to do nowadays is the same thing my dad was trying to do back in the 1950s and 1960s. He understood his patients. He had a long term relationship with them. He knew what social and psychological influences were affecting their health. He knew their standing the community. And he knew all this because he lived in that community for so long.

Well, we’re a more fluid society now, and medicine is more complicated now. So what we’re trying to do is carry some of that over. And what I’m trying to do is understand and preserve what was best about what my dad did in the modern age. The second part of the book has to do with this notion of community and what it’s been like to live here. It’s unusual for doctors now to be in the same community their entire career, and it’s actually more and more common for doctors to live in one community and practice in another.

Is that intentional?

Yeah, to some extent it’s intentional. They don’t want patients to run into them at the YMCA or the grocery store. They like that separation.

For me and for many primary care physicians immersion in the community is how we work. The community is a resource for us, not just a resource for the patients and their well being but also a resource for us in terms of our understanding of what influences their health. In the book I talk about eight patients who helped me learn how to be a good doctor. Many of them go back to my earliest days after arriving here, and some have continued to the present day, which is pretty neat.

Some of the same actual patients?

Yes, and they’re kind of a stand-in for all of the patients — my whole life here in this community. There is something enormously valuable about living in the community where you care for your patients, knowing them over a long period of time, and being established with them in multiple different kinds of relationships.

One day you’re their doctor, the next day they’re your car mechanic, the next day they’re your son’s teacher, the next day you teach Sunday school for their children. Whatever it is, we have multiple relationships and we see people in multiple different circumstances and that’s how I think we have an understanding of what they value, what they’re ready to change in their life, what they need to change in their life.

If I could sum it up in one sentence, it would be: I've learned how to reconnect people to their community when they've been disconnected by illness and aging, and how to disconnect people from their community when they've been steered down the wrong path through abuse and addiction. Some people need to be reconnected to their community, some people need to be severed from their community.

It seems like there’s an overlap into social work, if you were going to make hard distinctions.

If primary care were a three-legged stool, you would have a doctor, a social worker and a behavioral therapist. But when I was in medical training, that was never our understanding. The understanding was we had a toolkit. We had drugs and we had imaging studies and laboratory studies and procedures and we were going to fix people. Now what I realize is that it’s a very complicated process getting those who need to change to change and those who need to reconnect to reconnect.

You credit the title of your book to Paul Goldberger’s Why Architecture Matters.

Everything he says about architecture applies to family medicine.

You might have to explain that.

Yeah, basically he says this. He says “buildings tell us what we are and what we want to be and sometimes it’s the average ones that tell us the most.” Patients tell us who we are as doctors, who we need to be, for them, this day. Patients define who we are. That’s really what family medicine is all about.

You have younger people in your practice. How does that go at this point in your career? Are there times when you’re thinking things should be done a certain way, and they’re trying to plow ahead?

I think this will happen more the longer they’re here. They've just come, they’re new in practice, they’re just trying to keep their nose above water. But already, they have feelings and make decisions to do things differently than I would. And I say, good, you’re the future not me. But more to the point, they came here because they liked what we’re doing in our practice. And we try to change with the times. But yeah, that’s why at some point doctors need to stand back and let the new people coming in be the torchbearers. But I would like them to carry that torch with some understanding of what I value and what my dad valued in the work he did.

You’re not retiring.

No. Even though this is a capstone to my career it’s a little bit like the old guy who I talk about in my book. He lives a stone’s throw from the house he grew up in. I think he’s been west of the Kennebunk [River] once for an extended period of time. When I first met him, I asked him: Have you lived in Waldo County your whole life? And his answer was, well, so far. It’s the classic Maine saying and it’s kind of what I’m saying about the book.

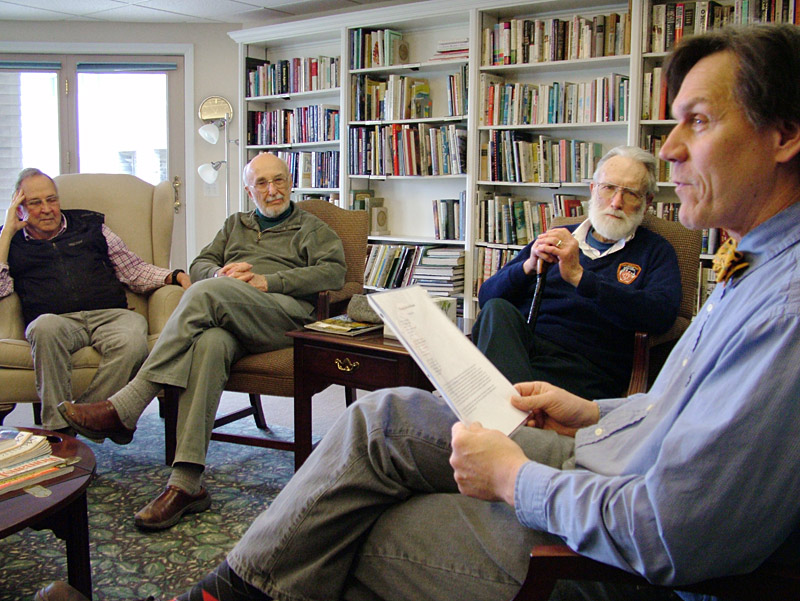

What’s the Old Duffers Club?

Essentially, it’s a group of guys who need conversation. They’re retired. Many of them don’t drive anymore. They’ve given up the home they lived in for many years. They’ve lost their first wife. Many of them are remarried. Lots of changes. And for most of us, as men, we’ve lost the knowledge of how to have a conversation outside of the context of our work. So this is an opportunity for them to get together once every two weeks with men their own age, going through their own problems, learning how to have conversation again and giving them a purpose for getting up in the morning again. Giving them something to do.

In the book you explain how you invented it during a routine diabetes check up with a male patient who began to cry while talking about a hunting trip with his son. How did it unfold?

Here’s a person who hadn’t exchanged a sentence with me for 20 years, now crying, showing an emotion that no old Mainer normally shows. And I said “So what’s going on? What are you thinking about?” and he just kept crying. He couldn’t put words to it. He didn’t know. So I volunteered, I said, “Are you thinking, how great to be with your son, to have this experience with your son, which may be the last time you’ll have this experience in your entire life?”

We’re now 10 minutes, 12 minutes into the exam. I could see that nothing was going to be accomplished that was on my agenda, so I said, “Roy, in two weeks we’re having a group of men your age, going through the same things you’re going through, getting together. I really think you’d be good for that group. I think you would have a lot to give that group. Would you be willing to come back and be a part of that group?” And he nodded that he would, which I was really, really surprised about. So for the next two weeks, I asked every old man I’d see in the office would they be willing to join a group of old men doing this, and surprisingly nearly everyone I asked was willing to try it. Some were in their late 60s early 70s, some were in their 80s, but they were willing to do this.

So the club didn’t exist before you had the conversation with Roy?

No, it began because of that conversation. I had to make it up on the fly, because it seemed like the right thing to do for him that day. And that’s really the basis of family medicine. What do they need that day? He needed a group of men just like him to immerse himself in.

So we got together and had 8 or 10 sessions and talked about what would be on your tombstone, what unfinished business do you have, what’s going to be in your will, just to begin talking about where you are in your life and how you’re preparing for the last chapter. After one meeting, a guy came up to me and said, Dr. Loxterkamp, how did you find 10 guys with so much in common? I had to respond honestly. I said, you were the first 10 guys I asked. And that’s just the nature of life, that we have a lot more in common with each other than we have differences.

For more information about What Matters in Medicine: Lessons from a Life in Primary Care, visit davidloxterkamp.com. The book is also available at Left Bank Books, 109 Church Street, Belfast.

Ethan Andrews can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com